EUDR Delay: A Setback for Orangutan Conservation?

- Jenny Taylor

- Jan 23

- 6 min read

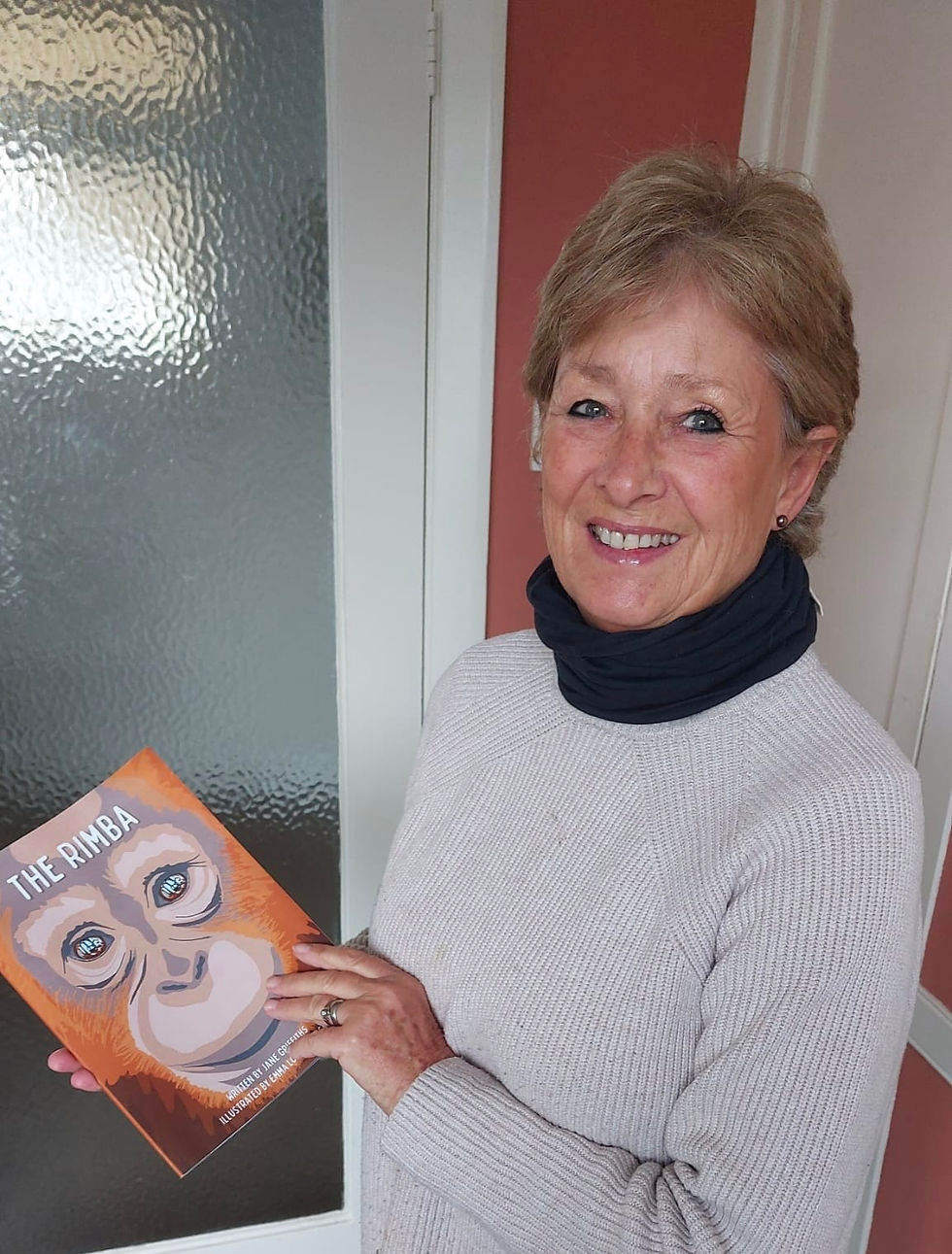

I recently participated in a webinar hosted by Innovation Forum called EUDR Unpacked: Palm and Soy Plantations Under the Lens, where I joined other panelists in discussing the reactions and impacts of the EUDR and of its postponement, with my focus on the implications for biodiversity. While I had only 5 minutes to “set the stage” plus time to engage in a Q and A with the other panelists, I gathered quite a bit of information to prepare myself. For this preparation, I researched what other environmental NGOs and experts were saying as well as interviewing many of them. This blog explores some of those findings.

As an orangutan conservationist, my focus is on palm oil and its impacts on forests and biodiversity, particularly in SE Asia. I started working on the palm oil issue more than 2 decades ago so and have seen the impacts of conventional palm oil first hand, as well as witnessed (and indeed played a comparatively large part in) the progress towards sustainable production and consumption of palm.

As an active participant in RSPO, SPOC, POIG and other platforms, I believe the attention given to this crop as well as the efforts to curtail deforestation associated with it, paved the way in many regards to the development of the EUDR.

A general feeling amongst many of my colleagues working in forest and biodiversity conservation and whom I interviewed for this webinar is that the EUDR legislationis a case of “Too little, too late” (and now even later). There is dismay that it misses out some ecosystem types such as savannah and wetlands, and that it doesn’t extend to other drivers of deforestation such as mining. (Though it should be noted that according to the think-tank Bruegel “The seven commodities it covers were responsible for 86.6 percent of tropical deforestation embedded in EU imports of commodities between 2005 and 2017.”) The 2020 cut-off date, says Forest Watch Indonesia for example, “seems to forgive activities that caused deforestation before 2020. In fact, it should be much earlier.” They went on to say “The EUDR process didn’t involve many civil society organizations from Indonesia that are concerned about forest conditions. This makes several policies in the EUDR not in accordance with the actual conditions on the ground. Such as determining the cut-off date, definition of forest, deforestation, and degradation, and also the methodology for calculating forest cover, and so on.”

Several colleagues expressed concerns about how the EUDR will deal with smallholders who may be left out due to the difficulty in proving land rights and demarcation of boundaries. The result may be that supply chains become cleaner simply by leaving out smallholders. We need to figure out how to avoid cutting smallholder producers out of the market when companies have incentives to simplify their supply chains in response to the regulation. One colleague suggests that the legislation should simply not apply to smallholders, pointing to a more precise tool of Jurisdicational Approaches to solve the thorny issue of land tenureship and other difficult issues, at least for the interim, until the EU gains experience on smallholders.

NGOs by and large were very angered by the delay in the EUDR and campaigned right up to the last minute to encourage Parliament not to delay. Greenpeace called the delay “devastating.” Mighty Earth said, “Delaying the EUDR is like throwing a fire extinguisher out of the window of a burning building,” adding that, ““Delaying the EU’s zero deforestation law by just one year is a catastrophe and will result in the added destruction of over 200,000 hectares of precious forests worldwide due to the EU’s thirst for major forest-risk commodities like coffee, chocolate, beef, palm oil and soybeans.”

According to an analysis by Global Witness, “The proposed delay could drive at least 150,385 hectares of deforestation linked to EU trade, an area more than fourteen times the size of Paris.” Birdlife International compared the amount of deforestation to an area the size of Moscow. A forest clearance of this scale will accelerate climate change, devastate biodiversity, and increase the risk of even more floods, fires and droughts.

As the IUCN has identified 193 vulnerable, endangered, and critically endangered species across the globe which have palm oil as a major threat, the delay will of course result in continued heavy impact on these species.

Prior to the vote to delay, WRI said, “Given that the EU’s imports of commodities account for 13-16% of global deforestation, despite representing only 7% of the world’s population, its environmental footprint and consumer influence are disproportionately large. The world’s forests cannot afford another year without stronger protection.”

And the Bruegel think tank wrote, “The delayed implementation of the EUDR comes at a sensitive time politically, at the start of the 2024-2029 EU institutional cycle and following campaigning against climate and environmental policies by radical right and some centre-right parties in recent elections. More climate and environment regulation will be needed in the rest of the 2020s to meet the EU’s already-agreed targets.”

The delay has undermined Europe’s environmental credentials and its role as a global leader in the fight against climate change and biodiversity loss.

With biodiversity crises on the rise, we have not a moment to lose to combat deforestation.

When we zoom in on the potential impact of the EUDR in Malaysia and Indonesia, one message is clear: while all colleagues that I interviewed welcomed the EUDR, they felt it would make very little difference to deforestation where they worked. This is because the expansion of oil palm in Southeast Asia is on a downward trend. Most EU supply is originating in Southeast Asia and 93% of it is already certified by RSPO, so the desired impact will be marginal. Where it would have most impact perhaps in countries where there might be expansion. But those countries mostly supply to domestic markets.

A colleague in Sabah said, “Most of the forest loss that is going to happen for production of plant-based commodities has already occurred. Future loss will be due to mining of nickel, gold, rare earth metals and coal even inside “protected” forests. This was echoed by a colleague working in East Kalimantan, who says the biggest threat to the survival of orangutans there is now mining.

Forest Watch Indonesia went into more detail on the limitations of impact of the EUDR in Indonesia: ”In our opinion, the EUDR will not have a major impact on the forest situation in Indonesia. This is because:

a. In the future, new drivers of deforestation in Indonesia will no longer be the commodities in the EUDR. Currently, areas that still have a lot of forest are threatened by nickel mining, coal, food estates (rice fields, sugarcane, and cattle farms), and biomass.

b. Timber production will decline, as will timber exports. This is because of the multi-forestry business policy that allows companies to easily change the commodities traded. Now many companies are trying to change their work plans from trading timber to trading carbon.

c. Palm oil exports continue to decline, due to high domestic demand, one of which is for biofuel development.”

All in all, the NGOs that I looked at supported the intentions of the EUDR. The legislation has been called “important” and “ambitious.” Cat Barton, Palm Oil Lead from Chester Zoo said that the EUDR “could be the first global legislation which sends a clear message that consumers care about deforestation and the impact on wildlife.” The legislation could encourage and inform legislative measures in other markets such as the UK Due Diligence legislation and the New York Declaration (but perhaps less so for the US Forests Act due to the recent election results)

The EUDR sends an important signal to countries and companies involved in producing, importing and trading forest-risk commodities: As WRI says, The laws of major markets are finally catching up with the long-recognized need to decouple commodity production from deforestation.”

This ambitious regulation, aiming to reduce the EU’s international footprint on forests, would significantly help reduce greenhouse gas emissions — both within Europe and around the globe. It could also positively impact biodiversity, as well as promote sustainable production and consumption patterns.

Additionally, it could encourage and inform legislative measures in other markets. A robust and ambitious EU regulation — along with similar regulations in other consumer countries — can send a strong signal to the global market that commodities must be produced without resulting in forest loss to meet climate, biodiversity and sustainable development goals.

This of course means that ultimately, if not belatedly, the EUDR WILL positively impact biodiversity.

Watch the full Innovation Forum webinar here.

Comments